George Lucas and the Lost EditDroid

How a Failed Machine Rewired Storytelling

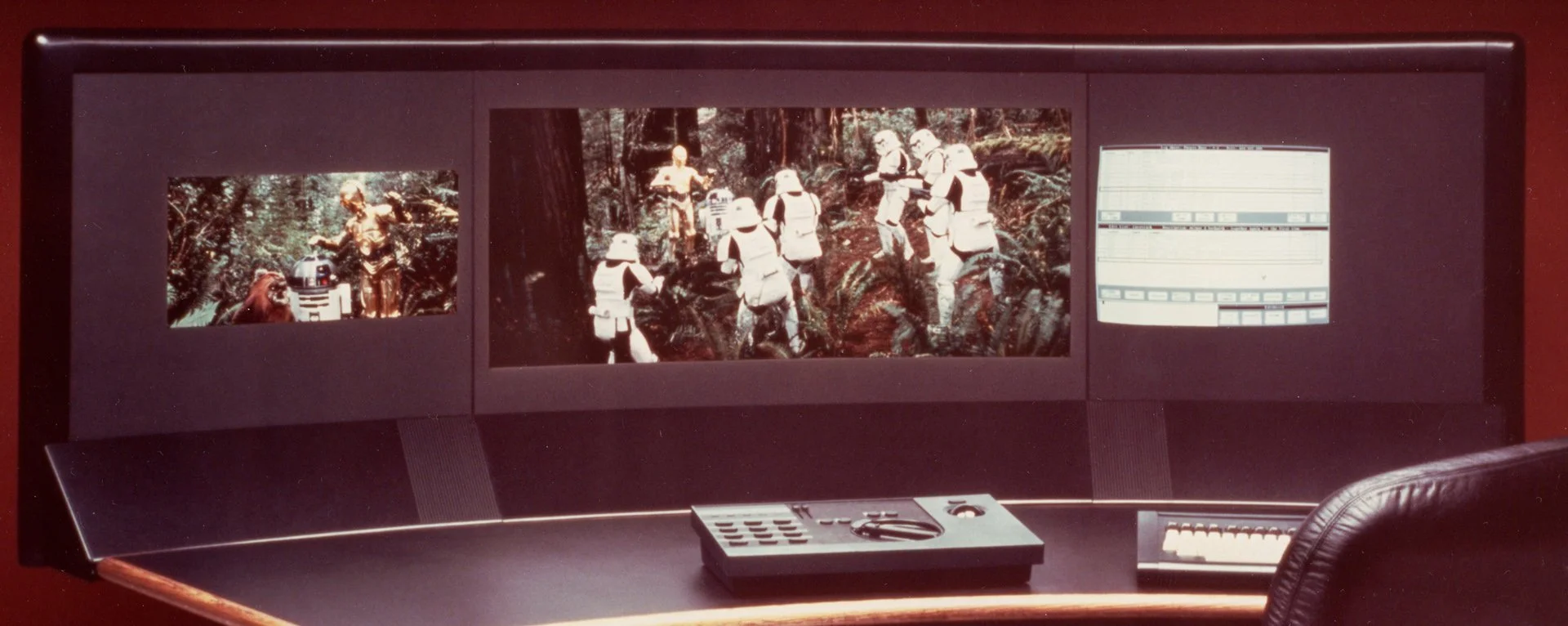

Picture an editing bay in 1984: reels stacked on metal shelves, the whir of a Moviola projector, film editors hunched over splicing tape with razor blades. Then imagine stepping into another room at Skywalker Ranch, where a glowing console looks more like a spaceship cockpit than a cutting bench. Screens display bins and timelines. A touchpad replaces the film splicer. For the first time, editors can jump to any frame instantly.

This was EditDroid, Lucasfilm’s radical leap into nonlinear editing. A system that promised to liberate storytelling from the slow grind of film reels. It would crash. It would fail. And yet, it changed everything.

The Tech That Was Too Early

When George Lucas invested $40 million in his Computer Division in 1979, he wasn’t just thinking about the next Star Wars. He was betting on technology that could change the way stories were made. The division, led by Ed Catmull (later Pixar’s co-founder), built three experimental tools:

SoundDroid (digital sound editing),

EditDroid (nonlinear picture editing),

And a research lab that would birth Pixar.

At the heart of EditDroid was an audacious idea: scan film into LaserDisc storage and edit digitally using a Sun-1 workstation with a graphical interface. Features included:

Random access: Jump instantly to any frame.

Timeline grammar: Clip bins, preview windows, and drag-and-drop editing, decades before it was standard.

Touchpad + jog knob: A hybrid of joystick and mouse for tactile control, at a time when “cursors” were still sci-fi.

The system wowed crowds at the 1984 NAB convention, where it was demonstrated with Return of the Jedi footage. But beneath the futuristic design, problems lurked:

Discs only stored 30 minutes per side, requiring towers of media.

Any revision meant pressing new discs.

Crashes were constant.

Costs were astronomical. Only a few studios could justify a machine that wasn’t production-ready.

Only about 24–30 EditDroids were ever built, and many ended up in storage or the dump.

A Moment in Film History

The EditDroid’s story runs parallel to a larger truth: Hollywood is often slow to embrace change.

Walter Murch, the legendary editor of Apocalypse Now, famously said editing was like “dreaming with your hands.” But for most editors in the 1980s, hands still meant grease pencils and scissors. Many distrusted the EditDroid, calling digital editing “unnatural.” Even Lucas himself never cut a feature on it, ironic, since he bankrolled its development.

There were, however, glimpses of promise:

Oliver Stone used it on The Doors and wanted it for JFK, before rental disputes derailed it.

Law & Order reportedly cut episodes on later redesigns.

Lucasfilm’s own Young Indiana Jones Chronicles became the system’s best showcase.

But while THX became the gold standard for sound and Pixar redefined animation, EditDroid withered. In 1993, Lucasfilm sold the system to Avid Technology, which was already gaining traction with computer-based nonlinear editors.

By the mid-90s, Avid, Final Cut Pro, and eventually Adobe Premiere carried forward EditDroid’s DNA. The timeline interface, jog controls, and bin-based workflows were no longer novelties, they were the backbone of modern editing.

As Michael Rubin wrote in Droidmaker:

“George’s stamp on nonlinear editing was the EditDroid… but in the end, it was Walter Murch who legitimized Avid.”

The EditDroid team with George Lucas (center, seated) and sound designer and editor Ben Burtt (right, seated). Ralph Guggenheim is seated behind Lucas. Standing are team members (L to R): Andy Cohen, Rob Lay, Kate Smith-Greenfield, John Lynch, David Blomgren, Steve Schwartz, Pete Ronzoni.

Lessons for Writers & Storytellers

The EditDroid may feel like a footnote in film history but for us, writers, filmmakers, storytellers, it carries deeper lessons.

It’s not just a relic of failed technology; it’s a reminder that every creative tool, no matter how flawed, reshapes the possibilities of how we tell stories. Behind the blinking lights and fragile discs was a vision: to free imagination from the limits of scissors and tape, to let storytellers move faster than the medium itself. That vision, even in failure, still speaks to us.

Failure Can Be a Blueprint

The EditDroid “failed,” but its core concepts became the foundation of digital editing. Creative innovation often looks like failure at first, but what matters is what survives.

Tools Shape Storytelling

Lucas wasn’t a technician, but he understood this truth: the speed and freedom of your tools affect the way you create. He wanted editing to be as fluid as writing, where you could experiment endlessly without penalty.

The Pioneer’s Burden

Being first is messy. EditDroid was too far ahead of available storage and computing power. Writers often wrestle with the same dilemma, publishing an idea before its time. Don’t be discouraged. What looks premature today can echo in the future.

Design With Empathy

The team interviewed dozens of editors to make the system familiar. They knew that radical tools need bridges, not cliffs. Writers, too, must build bridges to their audiences when experimenting with form.

The EditDroid console on display with Return of the Jedi footage. Lucasfilm’s attempt at nonlinear editing looked like science fiction decades ahead of its time.

When “Failure” Writes the Future

The EditDroid sits somewhere between triumph and tragedy; a gleaming console gathering dust in a Lucasfilm archive, and a ghost humming inside every modern editing system.

Its lesson is simple: storytelling evolves not just with imagination, but with the tools that set imagination free. George Lucas dreamed of editors who could cut without limits. We live in that world now, clicking and dragging on timelines born from a machine that never really worked.

Sometimes, the most important stories are told by the failures that came first.